Geometry

The Foundation |  |

The Double Gyres | |

The Cones | |

The Diamond and the Hourglass | |

The Phases of the Moon | |

The Wheel | |

The Faculties | |

The Principles |

The Foundation

When Yeats published �The Second Coming� in book form in 1921, he decided that he needed to explain the source of some of his imagery and thinking. He couched the account in terms of the fiction of Michael Robartes and Owen Aherne (see The Fictions of the Two Versions), giving a succinct summary of some of the main elements in the System that was emerging in his collaboration with George. Robartes gives Aherne �several mathematical diagrams�, �squares and spheres, cones made up of revolving gyres intersecting each other at various angles, figures sometimes of great complexity�, but the explanation for these �is founded upon a single fundamental thought. The mind, whether expressed in history or in the individual life, has a precise movement, which can be quickened or slackened but cannot be fundamentally altered, and this movement can be expressed by a mathematical form� and this form is the gyre. (See text of the note at the bottom of the page.)

Robartes/Yeats compares the inevitable pattern of this movement to the growth of a plant or animal, each species having its own variation of the fundamental paradigm, and each individual within a species being affected by its resources and circumstances, and he compares the paradigm to the laws of genetic inheritance discovered by Gregor Mendel. The gyre starts at its origin and moves progressively wider in a spiral, while time adds another dimension, creating the form of the vortex or funnel. Once the gyre reaches its point of maximum expansion it then begins to narrow until it reaches its end-point which is also the origin of the new gyre. Another way of seeing the same thing, if time is not taken as being fixed in one direction, is that once the maximum is reached, the gyre begins to retrace its path in the opposite direction. The gyre can therefore be seen as a single vortex which grows and dwindles, but the more commonly used figure is a double vortex, where two vortices intersect and the apex of one is at the centre of the other's base. The Double Gyres

Yeats's thought is fundamentally dualistic and, although the single gyre contains a fundamental dualism in the two boundaries of its form, the base and the apex, it is more natural for Yeats to use a doubled form. Since the apex or minimum of one element implies the maximum of its dualistic opposite, these double cones intersect so that the two gyres are the complementary opposites of each other.

In this formulation, if each gyre is depicted as a single principle, then the gyre moves from the total preponderance of one principle over the other, through increasing admixture of the second principle to equality at the point where the surfaces cross each other, until the minimum of the first and the maximum of the second principle are reached. At this point the reflux starts, so that there is never more than a momentary predominance of either principle, and the system is constant movement.

Classically, this is the kind of interrelation depicted in the Yin-Yang mandala or in any form of wheel expressing two polar opposites. As in the representation of the Yin-Yang polarity, the maximum of one gyre contains the minimum of its opposite at its centre, so that, even as this minimum briefly touches zero, it is still inherent within the whole. Yeats uses the cycle of the Moon's phases as the visual symbol of the interplay between his two defining principles, the Tinctures, primary and antithetical, the poles of which are symbolised by the dark of the Moon and the full Moon. Although this is shown as a disc divided into shaded and white halves in A Vision (AV B 80), it is more accurate to depict it as a disc where black and white are the extremes, with shades of grey in between.

The two diagrams represent the same idea, of two interacting principles which increase and decrease in a reciprocal relationship with each other. There are no fixed stages and the change is gradual rather than discrete, however once the cycle is applied to human life, death and birth mark radical changes of state for the human soul, and it becomes both natural and necessary to mark these divisions, which Yeats takes as the twenty-eight stages symbolised by the Phases of the Moon (see the Wheel). Even within history, where the transitions are not marked and are clearly gradual, the Phases provide a useful notation to show the point that the cycle has reached, so that they are maintained, or adapted to a twelvefold scheme (see the historical gyres). Especially with regard to history, it can sometimes be clearer to see the double intersecting cones extended over time, so that they become a chain rather than an isolated unit. This can appear to minimise the cyclical nature of the interaction, but can be helpful in disentangling the various cycles in operation at any one time (see History and the Great Year). |

The Cones

Because of the dominance of this image in Yeats's mind, even when he comes to refer to the supernatural opposite to mundane reality, he uses the term the Thirteenth Cone. There may also be some influence from Renaissance thinking here, where various writers posited intersecting pyramids of light and dark to represent the interpenetration of the divine and mundane, and to see in these two pyramids a ladder of descent from and ascent to the Godhead. Robert Fludd, the English Rosicrucian, created a fascinating series of diagrams which show the relationship of the Macrocosmic world of the divine to the Microcosmic world of the human.

The Diamond and the HourglassAlthough the double cone dominates the diagrams found in A Vision, the more important representation of the gyres in the Automatic Script was that which was called the �Diamond� and �Hourglass�, which is effectively a doubled form of the double cone. The Instructors objected to the term �Diamond�, but Yeats retained it anyway.  In A Vision this form of representation is most important in the discussion of the Principles, the spiritual constituents of the human being, which come to the fore in the after-life. In this system the axes of the two shapes do not necessarily coincide, and they rotate about a common centre, within a sphere. The Diamond itself represents the original Principle of the Celestial Body, within which the Spirit moves as a single gyre. These together form the Solar element of the system of the Principles, while the Hourglass represents the Lunar element. Both the Passionate Body and the Husk move within this double gyre, one half representing life and the other half the after-life (see the Principles and the After-life).  |

Note on 'The Second Coming', Michael Robartes and the Dancer (Dundrum: Cuala, 1921). Wade 127; the book was finished on All Souls' Day, 1920, and bears the date MCMXX on the title page, but was actually published in February 1921. |

|

Full text of the note on 'The Second Coming', Michael Robartes and the Dancer:

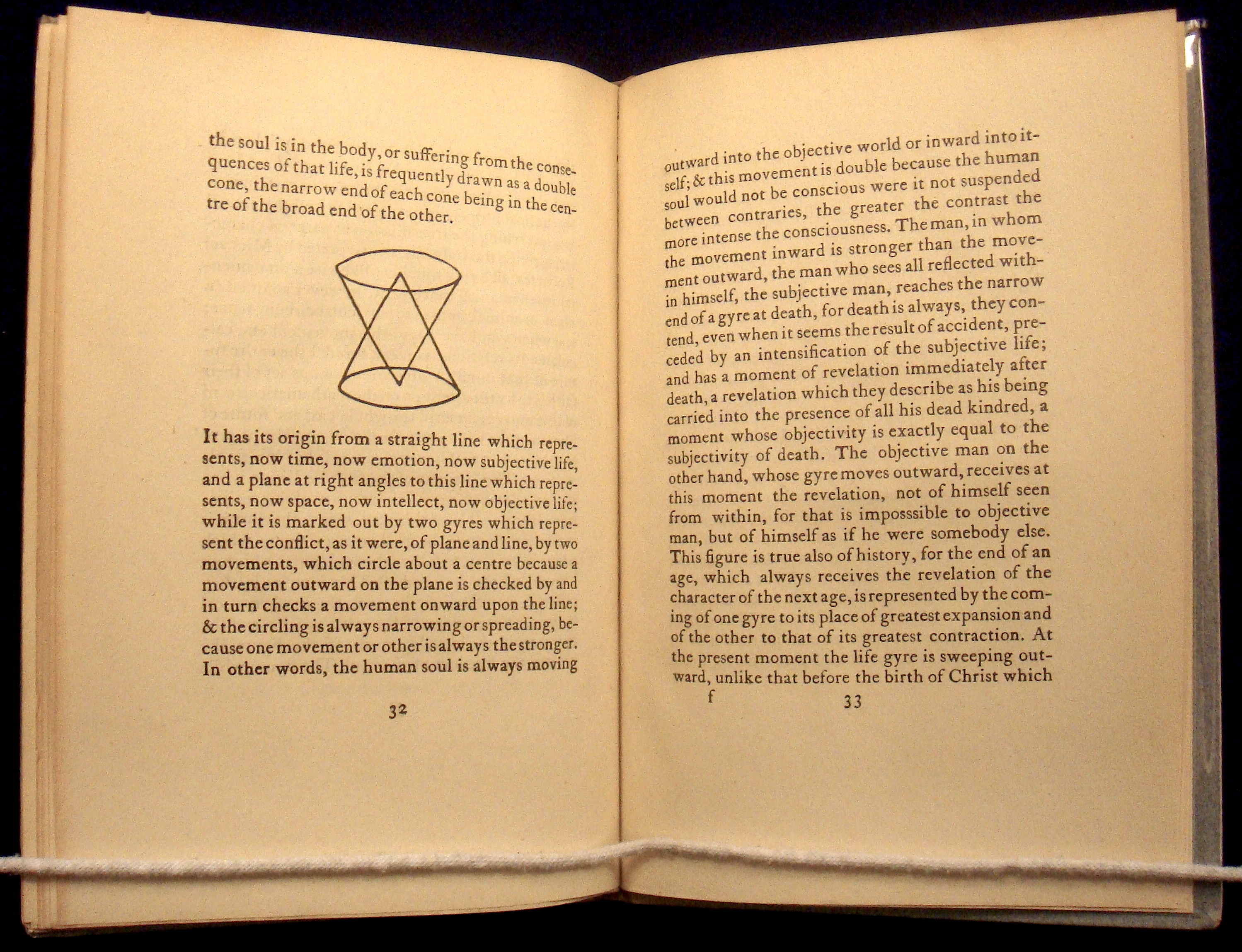

Robartes copied out and gave to Aherne several mathematical diagrams from the Speculum, squares and spheres, cones made up of revolving gyres intersecting each other at various angles, figures sometimes with great complexity. His explanation of these, obtained invariably from the followers of Kusta-ben-Luki, is founded upon a single fundamental thought. The mind, whether expressed in history or in the individual life, has a precise movement, which can be quickened or slackened but cannot be fundamentally altered, and this movement can be expressed by a mathematical form. A plant or an animal has an order of development peculiar to it, a bamboo will not develop evenly like a willow nor a willow from joint to joint, and both have branches, that lessen and grow more light as they rise, and no characteristic of the soil can alter these things. A poor soil may indeed check or stop the movement and rich prolong and quicken it. Mendel has shown that his sweet-peas bred long and short, white and pink varieties in certain mathematical proportions, suggesting a mathematical law governing the transmission of parental characteristics. To the Judwalis, as interpreted by Michael Robartes, all living minds have likewise a fundamental mathematical movement, however adapted in plant, or animal, or man to particular circumstance; and when you have found this movement and calculated its relations, you can foretell the entire future of that mind. A supreme religious act of their faith is to fix the attention on the mathematical form of this movement until the whole past and future of humanity, or of an individual man, shall be present to the intellect as if it were accomplished in a single moment. The intensity of the Beatific Vision when it comes depends, upon the intensity of this realisation. It is possible in this way, seeing that death itself is marked upon the mathematical figure, which passes beyond it, to follow the soul into the highest heaven and the deepest hell. This doctrine is, they contend, not fatalistic because the mathematical figure is an expression of the mind's desire and the more rapid the development of the figure the greater the freedom of the soul. The figure while the soul is in the body, or suffering from the consequences of that life, is usually drawn as a double cone, the narrow end of each cone being in the centre of the broad end of the other.

Their name means makers of measures, or as we would say, of diagrams. Variorum Edition of the Poems, 823-25. It is given in full in Richard Finneran, ed., W. B. Yeats: The Poems (2nd ed., 1997), 658-60, and (without the diagram) in A. N. Jeffares, W. B. Yeats: Poet and Man (1949), 197-98, (3rd ed. [1996], 175-77), though with variations of punctuation and sometimes wording. |

The essay "'Everywhere that antinomy of the One and the Many': The Foundations of A Vision," by Neil Mann in the collection W. B. Yeats's "A Vision": Explications and Contexts,

edited by Neil Mann, Matthew Gibson, and Claire Nally (Clemson

University, 2012), provides useful further exploration of this subject.

This title is available for free download here or here from Clemson University Press (click here if seems the link may have changed). It is also accessible online via Liverpool Scholarhip Online and University Press Scholarship Online (simplest to search on "Yeats" and "Vision"; direct link functional April 2016), though this is by subscription or through a library.