| The London Mercury November 1937 pp. 69-70 Seán O’Faoláin G792 |

MR. YEATS’S METAPHYSICAL MAN

By Seán O’Faoláin

VISION. By W. B. Yeats. Macmillan. 15s.

Mr. Yeats is daring; or, perhaps, arrogant. He has written a Sibylline book that I could easily imagine falling into this cynical, fragmentary, analytical age like a lark into a lime-kiln; as I can image it being read equally with pleasure and disgust, fascination and rage, seized on with glee by a Night and Day, trumpeted by a Hibbert Journal. And yet, what more analytical book has ever been written—unless, of another kind, the Anatomy of Melancholy? What more impersonal, aloof book? In this time of a return to the seventeenth-century poets (or have the Reds finished all that?) what more topical, of-the-period, classification of the contraries and opposites, the harmonious discords, in life and thought and the nature of man? If he had not been forced by his nature and his literary ancestry to wrap it up in a romantic fable of Michael Robartes, which will discourage many, if, that is, he could have written it in the crisp fashion of our day, I could imagine it echoing for a long time among the cognoscenti. Even yet it may—with whatever derision for its folly mingled with delight in its ripeness and wisdom.

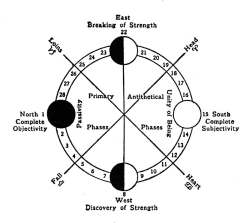

For years now Yeats has worked towards this book, teasing out his ideas about the contrast between fluid personality and static character, elaborating his fascination at the antinomies in man until he has, at last, in this book, come to “a classification of every possible movement of life and thought.” For this vast classification he uses a symbolism of interlocked, gyring cones, whose contraction and expansion bring the faculties of man into relationship with one another; to this he adds the symbolism of the waxing and waning moon to indicate the development of character, and its consolidation at given stages into certain typical conditions commonly found in life. The possible combinations of four faculties and twenty-eight phases are obviously immense.

|

The faculties are four—Will, or selfhood; Creative Mind, or thought; Body of Fate, or the thing we know, such as environment; and Mask, which is the desired or chosen Destiny, the Ought against the Is, the object of the will, or that (to borrow from Hindu philosophy, of which much of this Yeatsian metaphysic is evidently a development) towards which the Kharma moves, or is moved by will or desire, or chance, or fate.

Every man, proceeds the metaphysician, has these faculties in a special quality according as he is an Objective, Primary man, or a Subjective, Antithetical man. They are rarely in alignment or in harmony; for out of conflict comes the condition of life. Starting from complete objectivity, the progress is from character—the imposed unity, mob- and environment-formed—to self-won, or fate-given personality, a condition of fire; and thence back towards social character again. The illustration of all this by types, forms the most interesting part of the book, and must excite the brain of every pious reader. As we enter the Antithetical section of the Great Wheel, we thus come on the Image Burner (Savonarola), the Forerunner (Nietzsche)—the first type capable of Unity of Being—Sensuous Ego (Baudelaire); the Obsessed Man (Keats); the Positive Man (Blake or Rabelais); until social character begins to dominate again with the intense but disillusioned Emotional Man (Arnold) and the Concrete Man (Shakespeare); we pass on with Wells, Shaw, George Moore—Acquisitive Men—through men like AE, dependent on local conditions, obsessed by social conscience, and not capable of personal expression, to the Saint (Socrates) and the Fools of Shakespeare. It is all shrewd and persuasive though too many types are taken from men of letters. And when I begin to test with, say, Tchekov or O’Connell, I got an uncomfortable feeling that it was like the fortune-teller’s “dark man” and “fair man” which inveigles only the predisposed.

There is no ethic, no morality. The actor and the play are one. The drama is inclusive and illuminating—as absolute as a poem; a poem—however prosy with tables and numbers—whose subject is the oldest subject in the world—the nature of man in relation to his human destiny. With such a subject and such a poet, I cannot (once the pseudo-romantic trappings have been flicked away) imagine anybody form an assayer to a tea-tester, a Communist to a pious Roman Catholic, who will not find it an exasperating, provoking, stimulating delight.

It is the Yeats who loved Blake and Shelley, who detested Sargent and admired Whistler, who wished he could prefer Chaucer to Shakespeare, who disliked the Flemish satirists, who has always been seeking a unifying image and bewails the falling asunder of life before the fraying of the intellect; it is the Yeats of the personal, fiery poems, the dramatic, hammering, and hammered poems of the middle and later period; and nobody who would read these poems in a mood with the poet, extract from them the ultimate pleasure of their implications and overtones, can afford not to wind his way, with this book, into their cavern-sources in one of the most complex and solitary minds among lyric poets since the death of Keats.